Women in Chinese Religious Literature

Autumn Quarter 2020 Tuesday and Thursdays 4:30-5:50pm

Instructor: Kali Nyima Cape

Office: Gibson s-366

Office Hours: MTWRF 12pm-2pm

Meetings also available by appointment

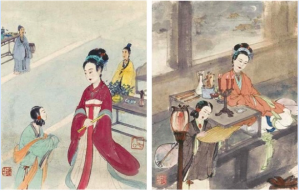

Image: The Empress Wu Zetian 1960, Artist Fu Baoshi 1904-1965

“Biographies of women, often depicted as marginal or oppositional figures,

can provide a historian with information about contradictions in social systems,

arguments or disputes about those systems,

including attacks on them and justifications for them. ”

– Cahill, Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood

This course examines elements of Chinese religious thought and activities as they appear within narratives about women. In order to introduce varieties of Chinese literature, the course will cover women in early China, in Confucian thought, in Daoism and Buddhism from the Han through the Tang dynasty. As the above quotation from Cahill suggests, taking marginal figures as a lens to study culture can expose themes that would otherwise remain invisible. We will examine the complex negotiation between religious and philosophical ideals and women’s lives. While themes of female lives such as motherhood, sexuality and fertility may at times be viewed positively, women in Chinese religious literature were clearly subject to inferior status and suppression. However, despite limitations of a patriarchal and patrilineal society, they negotiated with these elements and thus were agents within their sphere of influence.

This course will explore how female agency, self-definition, control and influence over religion and culture persistently took place despite limited patriarchal contexts. Therefore, the oversimplified colonialist assumption of Chinese women as passive victims will be contested, even while also highlighting restrictions placed on women based on gender in these cultures. We will consult a variety of sources including canonical texts, narratives, letters and even archeological evidence. Most predominant is the use of narratives. Narrative is a useful lens through which to observe Chinese history. Narrative does not impose the artificial boundaries between China’s great religions – popular religion, Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism. Within narratives, and likewise in Chinese culture, ideologies of these traditions intersect. Narratives also cross social, economic and geographical boundaries. While narratives cannot necessarily be generalized or representative, they communicate discernible themes of cultural and religious thought and activity. They evidence negotiations between philosophical principles and typical life circumstances. The narratives we will read are positioned alongside canonical texts throughout the readings. Thus, this lens will offer an accessible and digestible medium to engage with the topic of Women in Chinese Religious Literature, while also introducing key elements of philosophy, religion and culture.

Assignments

Complete the assigned readings for each week by Monday. Be prepared to dialogue about the questions for each week, listed in “Themes and Questions, ” section of the Schedule of Assignments. The main assignment for the course is a 20-page paper and therefore fulfills the writing requirement for undergraduates. Papers must be submitted by the due date. Every day the paper is late will result in a drop of half a letter grade. All papers must be in Times New Roman font, size 12, double spaced, with one-inch margins, and include properly formatted footnotes and bibliography (guidelines will be distributed). The maximum length is 20 pages. Papers not following these guidelines will also be downgraded half of a letter grade.

Final Paper Instructions

Choose one of the stories from Exemplary Women of Early China, Immortal Sisters or Lives of the Nuns. Analyze the story to show which principles of the three teachings of Confucian thought, Daoism or Buddhism can be found in that story. Re-write a version of the story according to the other two religious cultures, including elements that would be distinctively Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist. Interpret your stories and explain why you chose these elements. Include a Bibliography in Chicago Style format and at least four citations within the paper. Interpret and analyze any quote that you include in the paper. Organize the paper with an introduction, conclusion and clear thesis which is argued and explained throughout the paper consistently. The papers will be due at the end of the exam period at 5pm. Submit the papers online via drop-box.

Grading

Grades will be calculated as follows:

Participation 25%

Attendance 25%

Paper Draft 25%

Final Paper 25%

Required Textbooks (Available at the Bookstore)

Morton, Scott W and Lewis Charlton M. China: Its History and Culture. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2004.

Overmyer, Daniel E. Religions of China: The World as a Living System. 1st edition. Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc., 1998

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Tsai, Kathryn Anne. Lives of the Nuns. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994.

Other Assigned Readings (PDFs will be provided)

Bantly, Francisca Cho. Archetypes of Selves: A Study of the Chinese Mytho-Historical Consciousness. In Myth and Method, edited by Laurie L. Patton and Wendy Doniger. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996. 177- 207

Behnke-Kinney, Anne. Death by Fire, The Story of Bo Ji, Traditions of Exemplary Women. http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/xwomen/boji_essay.html. Accessed 15 Jan. 2021.

Behnke Kinney, Anne. Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienu Zhuan of Liu Xiang. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014. 1.1; 1.2

Behnke-Kinney, Anne. “Women in the Confucian Analects,” in Companion to Confucius, edited by Paul Goldin. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley and Blackwell, 2018. 148-163

Bell, Catherine. “Religion and Chinese Culture: Toward an Assessment of ‘Popular Religion.’” History of Religions, vol. 29, no. 1, 1989, pp. 35–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1062838. Accessed 15 Jan. 2021.

Berthrong, John, and Evelyn Berthrong. Confucianism: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2000. 1-76

Cahill, Suzanne E.. Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood: Records of the Assembled Transcendents of the Fortified Walled City, by Du Guangting. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2006. 850-933

Cole, Alan. Mothers and Sons in Chinese Buddhism. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1998). 159-235

Confucius. The Essential Analects: Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary. Translator, Edward Slingerland. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing, 2006. vi-xxii; 4-9, 38-40

Despeux, Catherine, and Livia Kohn. Women in Daoism. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2005.

Doniger, Wendy. Woman Who Pretended to Be Who She Was. New York: Oxford University Press (US), 2005. 177–207

Eliade, Mercea. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or, Cosmos and History. Reprint edition. Princeton University Press, 1971. Ix-37.

Englert, Siegfried and Roderich, Ptak. Nan-Tzu or Why Heaven Did Not Crush Confucius. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 106.4 (1986): 679-686. JSTOR. Web. 10 May 2015.

Geertz, Clifford. Centers, Kings and Charisma: Reflections on the Symbolics of Power. Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual, and Politics Since the Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

Kohn, Livia. Laozi: Ancient Philosopher, Master of Immortality and God. Religions of China in Practice. Ed. Donald S., Lopez. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996. 52–63

Ivanhoe, Philip J. Ethics in the Confucian Tradition: The Thought of Mengzi and Wang Yangming. 2nd edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2002. 1-12

Mann, Susan and Cheng Yu-yin Eds. Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 17-28, 43-69; 149-153

Mengzi, and Bryan W. Van Norden. The Essential Mengzi. Hackett Publishing, 2009. Kindle Edition. 31-32

Schafer, Edward H. “The Jade Woman of Greatest Mystery.” In History of Religions 17.3-4 Current Perspectives in the Study of Chinese Religions (1978): 387-398.

Shelach-Lavi, Gideon. The Archaeology of Early China: From Prehistory to the Han Dynasty. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 7-12; 45-49; 61-62; 81-86

Schipper, Kristofer. The Taoist Body. Trans. Karen C. Duval. Berkely and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1994.

Shin-yi, Chao. “Good Career Moves: Life Stories of Daoist Nuns of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries.” Edited by Harriet Zurnorfer. In Nan N: Men, Women and Gender in China vol. 1 no. 2. (Brill 1999). 10.1: 121-151

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 7-12, 43-48, 105-116, 119-125

Watson, Burton trans. Basic Writings of Mo Tzu, Hsun Tzu, and Han Fei Tzu. New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1967. 1-38

Watson, Burton. The Tso Chuan: Selections from China’s Oldest Narrative History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992. 20-25; 26-29; 30-38; 40-44; 45-49

Weber, Max. On Charisma and Institution Building. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

Wai yee, Li. The Readability of the Past in Early Chinese Historiography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007. 114-116.

Yao, Xinhong Yao. An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. 139-178.

Schedule of Assignments

Week One

Introduction to the Study of Chinese Religions

Assigned Readings

Bell, Catherine. “Religion and Chinese Culture: Toward an Assessment of ‘Popular Religion.’” In History of Religions 29.1 (1989): 35–57.

Eliade, Mercea. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or, Cosmos and History. Reprint edition. Princeton University Press, 1971. IX-37.

Morton, Scott W and Lewis Charlton M. China: Its History and Culture. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2004. 1-10; 14-21

Themes and questions

- What is “religion?”

- What are possible definitions for “Chinese Religions?”

- What are “myths,” and what functions do they serve? How are “myths” different from history?

Week Two

The Beginning of the World; China’s Mytho-Historical Consciousness

Assigned Readings

Kinney, Anne Behnke. Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienu Zhuan of Liu Xiang. Columbia University Press, 2014. Lienu Zhuan 1.1; 1.2; 1-4.

Overmyer, Daniel E. Religions of China: The World as a Living System. 1st edition. Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc., 1998. 1-117

Shelach-Lavi, Gideon. The Archaeology of Early China: From Prehistory to the Han Dynasty. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 7-12; 45-49; 61-62; 81-86

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 7-12

Themes and Questions

- How did Chinese civilization begin?

- What is the role of narrative in religion?

- What are forms of early Chinese religious thought?

Week Three

Sanctioned Selves & The Mandate of Heaven

Assigned Readings

Bantly, Francisca Cho. “Archetypes of Selves: A Study of the Chinese Mytho-Historical Consciousness.” In Myth and Method. Edited by Laurie L. Patton and Wendy Doniger. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996. 177–207

Behnke Kinney, Anne. Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienu Zhuan of Liu Xiang. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014. 135-136; 6-8

Morton, Scott W and Lewis Charlton M. China: Its History and Culture. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2004. 22-28

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998. 1-26

Wai yee, Li. The Readability of the Past in Early Chinese Historiography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007. 114– 116.

Yao, Xinhong Yao. An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. 139-178

Themes and Questions

- What resources do early Chinese Religions offer for identity construction?

- What is the “Mandate of Heaven” and how does it serve to legitimate leaders?

- What is the role of myth in religious interpretations of history?

Week Four

The Dynastic Imperative and Demonic Beauties

Assigned Readings

Behnke Kinney, Anne. Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienu Zhuan of Liu Xiang. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014. 135-156.

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1998. 61-86.

Watson, Burton. The Tso Chuan: Selections from China’s Oldest Narrative History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992. 20-25; 26-29; 30-38; 40-44; 45-49

Themes and Questions

- What is the concept of dynastic power? In early Chinese religions who is responsible for sustaining dynastic power and passing it on?

- What are the most important positions of power in relationship to dynastic stability?

- What is the ruler’s familial structure? What is the ideal role of the concubine and the concubine’s children?

Week Five

Confucian Women & Filial Piety

Assigned Readings

Ivanhoe, Philip J. Ethics in the Confucian Tradition: The Thought of Mengzi and Wang Yangming. 2nd edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2002. 1-12

Mann, Susan and Cheng Yu-yin Eds. Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 43-69; 149-153

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998. 195-234

Watson, Burton trans. Basic Writings of Mo Tzu, Hsun Tzu, and Han Fei Tzu. New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1967. 1-38

Themes and Questions

- What distinctions between the sexes are made in Confucian classics?

- What is filial piety and why is it important? How is Women’s filial piety similar or different to that of men’s?

- What are women’s roles in Confucian culture?

Week Six

Confucian Texts & Ritual

Assigned Readings

Behnke-Kinney, Anne. “Death by Fire, The Story of Bo Ji,” Traditions of Exemplary Women. http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/xwomen/boji_essay.html

Behnke-Kinney, Anne. Exemplary Women of Early China. New York, Columbia University Press, 2014). pp 68-70.

Behnke-Kinney, Anne. “Women in the Confucian Analects,” in Companion to Confucius, edited by Paul Goldin. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley and Blackwell, 2018. 148-163

Englert, Siegfried and Roderich, Ptak. “Nan-Tzu or Why Heaven Did Not Crush Confucius.” Journal of the American Oriental Society. 106.4 (1986): 679-686. JSTOR. Web. 10 May 2015.

Confucius. The Essential Analects: Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary. Translator, Edward Slingerland. Hackett Publishing, 2006. vi-xxii; 4-9, 38-40

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 43-48

Yao, Xinhong Yao. An Introduction to Confucianism. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 16-69.

Morton, Scott W and Lewis Charlton M. China: Its History and Culture. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2004. 29-70

Themes and Questions

- Review of major themes of Chinese culture in the Han dynasty: Family as the central unit, family succession, dynastic history, ancestor veneration.

- Review of the religions of China: Confucian thought and its literature.

- How are women depicted in the Analects?

- What forms of ritual are illustrated in the story of Nan zi? Why is ritual observance important in Confucian society?

Week Seven

Confucian Social Structure

Assigned Readings

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 105-116

Berthrong, John, and Evelyn Berthrong. Confucianism: A Short Introduction. Oneworld

Publications, 2000. Print. pp 1-76

Themes and Questions

- What are women’s roles in Confucian society?

- What virtues are important for women in the family structure and why?

- Do women have power within their families and if so what kind?

*First Draft of Paper is Due Next Week

Week Eight

Confucian Charisma: ‘De’

Assigned Readings

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998. 27-59; 235-257

Themes and Questions

- What is virtue in the Confucian context?

- What is charisma in the Confucian context? How it is derived and actualized?

- Can women have De?

*First Draft of Paper Due

Week Nine

Daoism; Laozi and His Mother

Assigned Readings

Kohn, Livia. “Laozi: Ancient Philosopher, Master of Immortality and God.” Religions of China in Practice. Ed. Donald S., Lopez. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1996. 52–63

Morton, Scott W and Lewis Charlton M. China: Its History and Culture. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2004. 38-44

Overmyer, Daniel E. Religions of China: The World as a Living System. 1st edition. Waveland Press, Inc., 1998. 32-39

Schipper, Kristofer. The Taoist Body. Trans. Karen C. Duval. Berkely and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1994. 119-129

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 71-81

Themes and Questions

- Describe the roots of Daoism. What needs did it fulfill? Why kind of imagery is used in the Tao-te ching and why?

- What is the role between the celestial beings and humans in Daoism?

- Who is Lao Zi? What is significant about Lao Zi’s birth story?

Week Ten Daoism

Body Cosmology, Alchemy & Mysticism

Assigned Readings

Despeux, Catherine, and Livia Kohn. Women in Daoism. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2005. Read: Women and Cosmic Yin 9-13; “Women’s Transformation” 177-221.

Cahill, Suzanne E. Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood: Records of the Assembled Transcendents of the Fortified Walled City, by Du Guangting. 850-933. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2006. 1-33; 43-69

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998. 139-168

Schafer, Edward H. “The Jade Woman of Greatest Mystery.” History of Religions 17.3-4 Current Perspectives in the Study of Chinese Religions (1978): 387-398.

Themes and Questions

- What is the purpose of Daoist meditation?

- What is Alchemy? How are the primary principles: yin, yang and qi understood?

- What is the Daoist concept of the body?

- How does sexuality relate to this paradigm? The term ‘self-cultivation’ was also used in the Confucian context. What does ‘self-cultivation’ mean in the Daoist context? How it is connected with ascension?

Week Eleven

Immortal Women & the Yin/yang Paradigm

Assigned Readings

Despeux, Catherine, and Livia Kohn. Women in Daoism. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2005. Read: Women and Cosmic Yin 9-13; “Women’s Transformation” 177-221.

Cahill, Suzanne E. Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood: Records of the Assembled Transcendents of the Fortified Walled City, by Du Guangting. 850-933. Cambridge,

MA: Three Pines Press, 2006. 1-33; 43-69

Raphals, Lisa Ann. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, 1998. 139-168

Schafer, Edward H. “The Jade Woman of Greatest Mystery.” History of Religions 17.3-4 Current Perspectives in the Study of Chinese Religions (1978): 387-398.

Themes and Questions

- What are women’s roles in Daoist Communities?

- How do narratives about female monastics function in Daoist Communities?

- Narratives of Two Daoist Matriarchs and One Heavenly Nun

Week Twelve

Buddhist Sex & Gender

Assigned Readings

Cole, Alan. Mothers and Sons in Chinese Buddhism. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1998) 1-13; 159-235

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 119-125

Themes and Questions

- An introduction to Buddhism in India and major Buddhist themes; the Buddha, the Four Noble Truths. How would the Buddha’s life story sound to a Confucian thinker?

- What are differences in Buddhist concepts of the family? How is the mother-son relationship understood in Buddhism and why?

- What is a Pure Land? How does belief in a Pure Land shape an individual’s life?

Week Thirteen

Emptiness & Equality of the Sexes

Assigned Readings

Sommer, Deborah. Chinese Religion: An Anthology of Sources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 126-143

Tsai, Kathryn Anne. Lives of the Nuns. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994. 27

Themes and Questions

- How does Avalokiteshvara, the buddha of compassion, become a female?

- How does the teaching of emptiness impact the notion of differences between male and females?

- How and why does Shariputra, the disciple of the Buddha, become a female? What does he learn?

Week Fourteen

Lives of the Nuns

Assigned Readings

Tsai, Kathryn Anne. Lives of the Nuns. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994.

Themes and Questions

- What do Daoism and Buddhism have in common?

- What elements of Confucian teachings are in conflict with Buddhist ideals?

- Why would women become nuns according to the text?